How (Programming) Languages Shape Problem Solving

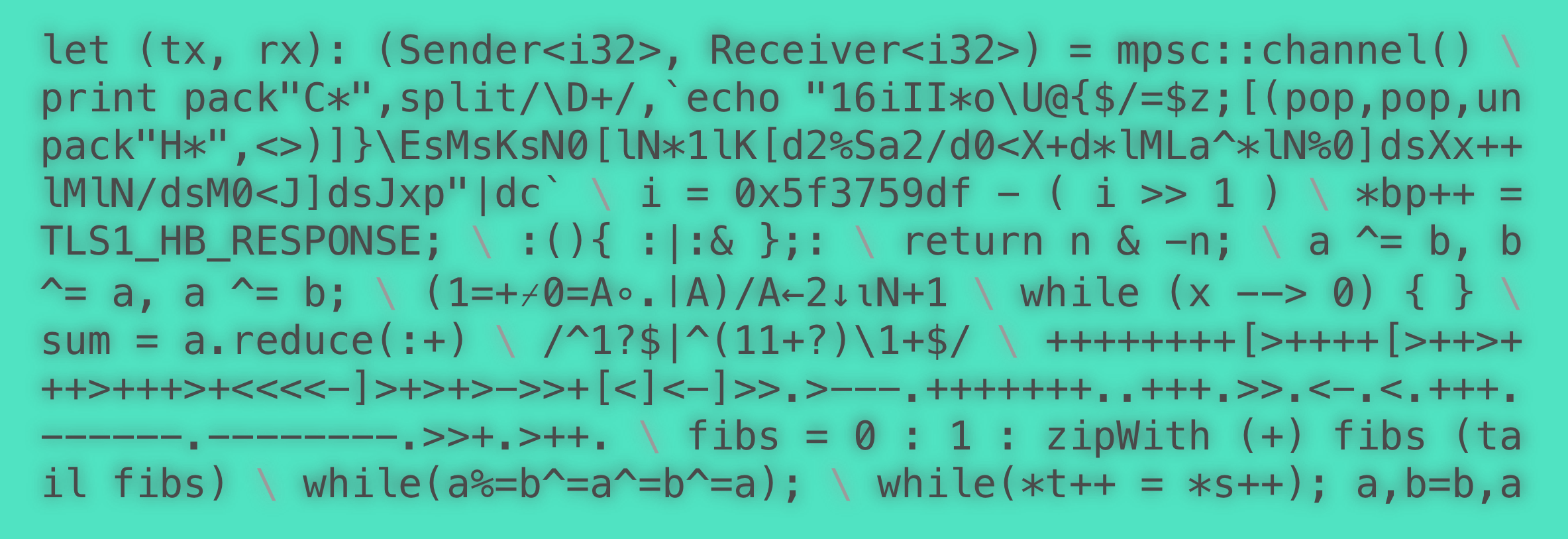

It is increasingly important to be a multilingual developer. Being a developer who is fluent in many programming languages not only helps your marketability, but it will also improve your problem-solving skills. It will help you become a more powerful developer who can tackle a problem with deeper insight, better-informed architectural decisions, and think beyond the inherent limitations of any single language. In the past six months,

I learned languages that I previously only used casually (like Ruby, Python, and JavaScript) in pursuit of staying at the leading edge of the evolving technological landscape. During this period, I have come to realize that my thinking and problem-solving in software engineering had been limited to what is idiomatic in Swift and Objective-C. Becoming a multilingual developer has improved my problem-solving skills.

A language and its design have profound consequences on its users. As a bilingual person, I have the benefit of being able to think through a problem in both my mother tongue as well as in English where I can take advantage of small differences between those languages. (For example, one language may have a very specific word for a concept while the other differs in grammatical structure that allows me to see the problem from a different angle.) Perhaps the best example of the impact of the design of a language comes from research on Magnetoreception (the perception of the geomagnetic field) which discusses languages throughout the world that lack words for egocentric directions (front, back, left, and right) and instead solely rely on cardinal directions (north, south, west, east).1The users of those languages have become extraordinarily aware of their sense of direction. Perhaps imagine if you had never learned the word for blue—how would that affect your perception of the world? There is even evidence that a higher percentage of tonal language speakers (such as Mandarin and Vietnamese) have absolute pitch — the ability to label the musical pitch of an arbitrary sound — than those who are not speakers of tonal languages.2 The design of a language has immense power to affect its speakers and their way of perceiving the world.

An influential linguist Edward Sapir once wrote that “The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same worlds with different labels attached."3 I believe this also apply to us as software engineers with programming languages: it is important for us as developers to invest the time and effort into learning unfamiliar programming languages.

For example, let’s say that you’re a junior iOS developer and have only ever read or written Swift, and never Objective-C. There are programming paradigms that you’re missing out on.4

Objective-C and Swift

One of the key differences between Objective-C and Swift is how functions are called. Objective-C implements its functionality by passing runtime messages between objects whereas Swift function calls must be known at compile-time. This has a few serious implications: it’s possible to compile and execute an Objective-C program where the object sending a message (i.e. a function call) doesn’t know anything about the recipient of that message. The opposite is also true: the object receiving a message may not know what to do with that message (i.e. missing function declaration). This means that in Objective-C, you don’t have to know what function call (i.e. message) your code is going to make when you compile your app. This messaging system (which can allow for a lot of abuse) enabled and continues to enable an incredible number of iOS and macOS applications and libraries that would not have been practical or even possible in Swift. (This is how Dropbox placed those green checkmarks in Finder before the official API became available in OS X 10.10 “Yosemite”).

Here is another example of what you’re missing out on if you’ve only ever written or read Swift:

Async & Await

Until recently, I had never used the async/await pattern. While I am intimately familiar with concurrency and the immense power of Grand Central Dispatch, I completely missed out on async/await.

One of the best things about working at Livefront is its emphasis on leadership in the software field and its future. On my most recent R&D project, I’ve had an opportunity to learn and use JavaScript (ES6) on the Node.js platform to puzzle together asynchronous network requests within a strict structure that I could not redefine (i.e. an SDK). This is usually not a challenge that I face in working with Swift and Objective-C given that I get to architect the asynchronous work in such a way that is both idiomatic and makes conceptual sense in my mind. However, working within a strict confines of an SDK on a server architecture I had never used before (AWS Lambda) in a foreign language proved a challenge that necessitated me to put my head down and learn a totally new concept: async/await.

After exploring JavaScript’s built-in support for async/await (and Promises!), I realized that I had done something similar many times in the past in Swift using Grand Central Dispatch’s DispatchGroup. However, the key difference was that Swift does not have language-level support for the await in async/await. (await prevents the execution of the code from continuing past the await keyword until the async has been resolved.) This has the power to enable a meaningful order of asynchronous operations as well as avoiding potential callback hell that can arise even in the best of Swift codebases.

Let’s look at an example:

| async function getMoviePackageFor(movie_id) { | |

| /// Get the URLs of the movie and subtitle file in parallel | |

| const movie_url = await MovieDatabase.getURLFor(movie_id) | |

| const subtitle_url = await SubtitleDatabase.getURLFor(movie_id) | |

| /* | |

| By the way, if you want those two async actions to run in | |

| parallel, you can do this: | |

| const [movie_url, subtitle_url] = await Promise.all([ | |

| MovieDatabase.getURLFor(movie_id), | |

| SubtitleDatabase.getURLFor(movie_id), | |

| ]) | |

| */ | |

| const movie_file = await DownloadTool.download(movie_url) | |

| const subtitle_file = await DownloadTool.download(subtitle_url) | |

| return [movie_file, subtitle_file] | |

| } |

Here is one (quite suboptimal) way in Swift to execute a similar operation only using Foundation:

| func getMoviePackage(for movieID: String, completion: MoviePackageFetchCompletion? = nil) { | |

| var movieURL: URL? | |

| var subtitleURL: URL? | |

| var movieFile: File? | |

| var subtitleFile: File? | |

| /// The `DispatchGroup` for the parallel URL fetch operations | |

| let urlFetchGroup = DispatchGroup() | |

| urlFetchGroup.enter() | |

| service.getURL(for: movieID, type: .movie) { result, error in | |

| guard error == nil else { | |

| urlFetchGroup.leave() | |

| return | |

| } | |

| guard let url = result.url else { | |

| urlFetchgroup.leave() | |

| return | |

| } | |

| movieURL = url | |

| urlFetchGroup.leave() | |

| } | |

| urlFetchGroup.enter() | |

| service.getURL(for: movieID, type: .subtitle) { result, error in | |

| guard error == nil else { | |

| urlFetchGroup.leave() | |

| return | |

| } | |

| guard let url = result.url else { | |

| urlFetchgroup.leave() | |

| return | |

| } | |

| subtitleURL = url | |

| urlFetchGroup.leave() | |

| } | |

| /// Commence downloading when URL fetch has finished for both | |

| /// types. | |

| urlFetchGroup.notify(queue: .main) { | |

| /// Exit early and trigger callback with error if either of | |

| /// the URLs are nil. | |

| guard let theMovieURL = movieURL, | |

| let theSubtitleURL = subtitleURL else { | |

| completion(nil, .serviceError) | |

| return | |

| } | |

| /// If both URLs are not nil, continue onto the download phase | |

| let downloadGroup = DispatchGroup() | |

| /// ... repeat with downloading files ... | |

| downloadGroup.notify(queue: .main) { | |

| guard let movie = movieFile, | |

| let subtitle = subtitleFile | |

| else { | |

| completion(nil, .serviceError) | |

| return | |

| } | |

| completion(MoviePackage(movie: movie, subtitle: subtitle), | |

| nil) | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } |

Clearly, this is why libraries like PromiseKit exist. (At Livefront, we’ve written a thin wrapper around URLSession that allows Promise-like chaining of tasks and error catching for network operations.) However, neither of these solutions enable the synchronous design that await provides should it be needed.

“The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same worlds with different labels attached.” - Edward Sapir

Had I not ventured outside of my usual routine of dependency-free Swift to explore ES6 JavaScript, not only would I have missed out on this particular programming paradigm, but I would have also missed out on the mental/conceptual model of async/await. Now that I’m familiar with this kind of control flow of combining asynchronous and synchronous code together, I have yet another tool in my toolbox that I can use at a moment’s notice in problem-solving. And, even though I can’t natively use await directly in Swift, I can borrow concepts from async/await to implement new idiomatic solutions.

.Finally()

If you’re saying to yourself “but I already knew about async & await!”, that’s awesome! And, you’re right: async/await is not a new idea. It has existed in C# since Visual Studio 11 and as far back as 2007 in F#, but that’s the point! I’ve learned many things exploring Ruby, Python, and JavaScript among other languages these past six months. I can confidently say that there is some pattern, architecture, or even a language-level feature that you probably aren’t aware of, and I hope that you will continue to explore other languages and features that will make you a better developer.

Keehun loves to find.out().then(obliterate(his.ignorance))at Livefront.

Footnotes

Thanks to Mike Bollinger, Pete Jones, Brian Yencho, Sean Berry, and Collin Flynn for their editorial support.

-

http://www.eneuro.org/content/early/2019/03/18/ENEURO.0483-18.2019 ↩︎

-

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/10/121023124000.htm ↩︎

-

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-biolinguistic-turn/201702/how-the-language-we-speak-affects-the-way-we-think ↩︎

-

If you are reading this, and you are a person who has only experimented with a single language (Swift or any other), I highly recommend you go check out other languages such as C++, Rust, Go, Java, R, C#, and Kotlin. ↩︎